I think a future flight should include a poet, a priest and a philosopher… we might get a much better idea of what we saw.

Michael Collins Apollo 11 astronaut 1969

Introduction

The recent launch and successful landing of the Perseverance Rover on the planet of Mars excited much public interest that have revived the interest in and inspiration created by space exploration. The public response, however, has been mixed in that it has been asked why spend so much money on exploring for water on Mars when some populations on Earth do not have direct access to fresh water. In some senses this is a fair point but one is not the opportunity cost of the other and thus directly comparable.

What this perspective loses sight of is the wider set of socioeconomic benefits of space exploration that are frequently overlooked that include cultural and symbolic aspects among others. For example, the International Space Station tracks weather conditions contributing to meteorology and water management among many others.

Evaluating socioeconomic benefits of space

Davis Bowie’s paen to life on Mars may have been realised through successive scientific missions seeking to answer this question. Although science is the datem from which knowledge flows there are other categories of benefit that spillover into economy and society. These include, inter alia;

- Inclusive economic growth;

- New Global Challenges;

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs);

- Societal Inspiration;

The European Space Agency (ESA) established variations of the categories above for its European Exploration Envelope Programme (E3P) established in 2016. ESA’s total budget from 2019 up to 2023 will be €14.4bn that although an apparently large number is the equivalent of a citizen within the 22 ESA Member States visiting a cinema once a week. In terms of benefits, these types of space programme tend to be upstream and downstream; direct and indirect. The former can lend themselves to quantitative measures whilst the latter stimulate the use qualitative measures.

In evaluating the economic impact of space exploration, Input-Output (I-O) Analysis, often complemented by Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) tends to be commonly used. Many of the studies using these methods tend tend to focus on more upstream and direct benefits, whilst concluding that more downstream and indirect benefits are often too difficult to estimate. There are also well established flaws in the methodology of CBA that can distort results.

I-O Analysis estimates the impact on associated industries based upon the World I-O tables by calculating national income, employment and fiscal multipliers. For the space exploration industry these tend to range from 1.8 to 2.3 so that for every €/$/£/Y spent nearly two times the amount of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) employment and net government revenue will be generated. These outcomes tend to be favoured by policy makers as they provide apparently hard results. However, the impact of space exploration on complementary and downstream industries and activities (automotive, aircraft production, sustainable energy and transport, health, design and architecture, among others) potentially change the composition of the World I-O tables in future and thus the size of the multipliers.

One method method for estimating and evaluating qualitative measures of socioeconomic benefits is to draw upon Pierre Bourdieu’s, the French sociologist, concept of economic capitals. The summary table below provides an illustrative list and simple definition

| Capital | Defintion |

| Cultural/ Symbolic | Cultural capital is the accumulated stock of knowledge available to citizens about the products of artistic and intellectual tradition that can provide the means to advance their status in society. Symbolic capital is the resources that an individual may access to promote their honour, prestige or recognition, and serves as the value that individuals hold within a culture |

| Educational | The provision and structure of resources that advance and disseminate knowledge to promote economic, societal and political aims. |

| Environmental | The natural resources, and benefits, essential for ecological sustainability and socio-economic activity. It also comprises negative values such as pollution, contamination, and climate change. |

| Financial | Resources that fund activities, create investment opportunities and result in the generation of national income and output, that contribute to economic growth and the distribution of income and wealth for societal benefit |

| Human | The accumulation of the knowledge, skills, expertise, competences and other attributes of people, including aspects of physical and mental well-being |

| Organisational | The processes, systems and structures within and between institutions. |

| Social | The sum of the resources that networks of individuals, groups and organisations gain as a result of mutual and recognised relationships that are institutionalised in any form. |

| Technological | The scientific innovation and practical application of knowledge in order to address the needs of the society. This takes different forms depending on the sector it is developed for. |

There are a number of measures that can be used to evaluate changes in each of these capitals as the basis of estimating qualitative measures of socioeconomic benefits created by space programmes.

The localisation of space benefits

The socioeconomic benefits of the co-location of industry and related activities can be captured by agglomeration economies of which there are three types, that the table below define.:

- Locational economies;

- Urbanisation economies;

- Activity complex economies,

| Agglomeration Economy | Definition and details |

| Localisation Economies | Localisation economies refer to the advantages accruing to the firm in the same activity which result from their joint location. On the revenues side… are the possibilities for the cross-referral of business among firms and the emergence of particular specialisations within the activity. |

| Urbanisation Economies | Urbanisation economies are concerned with the range of advantages to the individual firms which result from the joint location of firms in different and unrelated activities……….the availability of transport and communications facilities and municipal services may provide important savings |

| Activity-complex Economies | These are economies that emerge from the joint location of unlike activities which have substantial trading links with one another. In the case of manufacturing, such economies typically occur within industrial complexes, involving structures of a vertical or convergent nature. It is common to find these regions and urban localities in which there is a dominant Schumpeterian propulsive industry from which the three types of economy are realised: in this case the space industry. |

Like much of modern manufacturing, the space industry cuts across services as well. In line with modern trade that creates considerable internal and external transactions through Global-Value Chains (GVCs). Examples include industry-education co-location that generates and exploits agglomeration economies but also space agencies (for example, ESA) also create important local spillovers. These joint programmes make an important contribution to the space economy as a resource in cities and regions for which the space is the propulsive industry within their activity-complex economies from which socioeconomic benefits may flow.

One major space programme acts as an example of the role of the space economy and industry in creating localised socioeconomic benefits is the ORION-European Service Module (ESM).

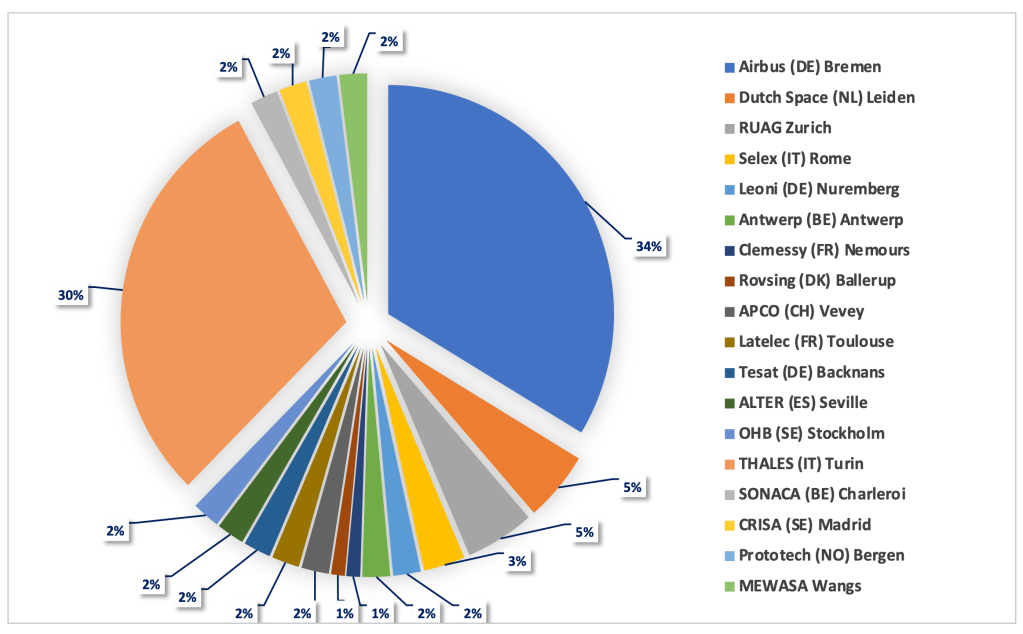

The ORION – ESM Gateway is a joint venture between ESA and North American Space Agency (NASA) to provide the European Service Module. The ORION capsule is the successor to the Apollo missions and a key component of the Artemis Lunar exploration programme. Assembled by Airbus in Germany but drawing upon in resources across 10 countries, the ESM is central to NASA’s ORION missions. The ESM-1 sits below the crew capsule and contains the main engine as well as four solar sails to supply power. It not only controls climate and temperature but is also responsible for the complete supply of fuel, oxygen and water to the spacecraft. ORION could not fly without the ESM that will orbit the Moon as the docking station for the ORION capsule. Two further versions of ESM have been contracted to be completed in 2021 and 2022 with a fourth planned for 2024.

The network of contractors and subcontractors includes more than 18 companies from 10 different European countries with an approximate value of €1bn (2018 prices) over the four ESMs. The contracts were awarded by ESA in accordance with its basic principles for procurement. It can be argued that as batch procurement is central to the successful manufacture of ORION-ESM. it can be viewed as a form of Organisational Capital. Moreover, a form that has been strengthened with each subsequent model.

There are two effects that arise from this development:

- Process: production decisions on quality management, employee programs, efficiency in operations and organisational flexibility. Companies that are well established and/or leaders in their field generally contribute a ‘process component’ in a network;

- Innovation: the ability of a company to create and develop new products and services, representing a fundamental aspect of competitive advantage. The potential for innovation is what makes the inclusion of start-ups and relatively new companies in a network.

There are a number of spillovers, some of which generate a number of innovation multipliers. These include factors such as network; navigation; telecomms; and, ESA membership. Summary work of international studies undertaken by London Economics on behalf of the UK Space Agency conclude that the multipliers range on average from 3 to 5.

The relative size and location of the ORION-ESM network is shown in the figure below:

The learning effects from the development of Organisational Capital from the ORION-ESM network also contributes to Industry 4.0 (I4.0) strategies and policies in the nations and places the network covers. Indeed, it specifically contributes o the evolution of the European Union’s (EU) and ESA’s Space 4.0 strategies.

Place-based Leadership as an enabling agency

The concept and practice of place-based leadership has stimulated increased interest in academic. policy and practitioner circles in recent years. Assigning a simple definition is challenging but the summary by Beer, Ayres, Clower, Faller, Sancino and Sotarauta in their 2018 paper provides a more comprehensive perspective :

Observations from contemporary place leadership studies locate it not in the attributes of individuals or government structures as such, but in the relationships connecting actors in specific places and various development processes. Place leadership is thus a scalable concept that may be used across different levels of spatial analysis (cities, sub-regions, regions, villages, neighbourhoods etc.) covering location (a specific physical location), locale (the construction of a multiplicity of social relations) and the sense of place (subjective emotional attachments).

There are a number of types of leadership of which Budd and Sancino suggest three:

- Managerial leadership: provided by public managers working in local government organizations;

- Political leadership: provided by the local political class and in particular by those local politicians that are in charge of implementing city programmes and plans (e.g. the Mayor – where established – and the members of the Cabinet);

- Civic leadership: provided by all the civic leaders operating outside the traditional realm of public sector, but that with their behaviours – both as individual and as individual representatives of non-profit or business organizations – contribute to the achievement of relevant city social outcomes.

Linking the definition and types of place-based leadership to the activity-complex economy in which space is the propulsive industry represents an important transition in realising its socioeconomic benefits in its localities and regions. The Organisational Capital produced by the ORION-ESM networks provides one example whereby place-based leadership is becoming an important agency for the localised benefits of the space economy and industry.

There is also an increasing numbers of pace city/regions that build on the industrial heritage of shipbuilding, aerospace, marine engineering, oil and gas automotive and associated industries. For example, Glasgow is the leading place for manufacturing satellites below 250Kg. Other UK space locales include, inter alia, Cambridge, Didcot, Edinburgh, Guilford, Harwell, Goonhilly, Oxford, Stevenage,and Yeovil. The UK Spaceport programme s alos stimulating the development of space-based locales and in which place-based leadership is a key agency.

There are also a number of regional Space Catapult centres. Across the rest of Europe there are a number of renowned cities and localities some of which host ORION-ESM activities.

All in all the genesis of place-based Leadership of Space City/Regions is making an important contribution to realising the socioeconomic benefits of space exploration for citizens in new and old places.

goi